Investing When The Sky is Falling

Kobe Bryant died due to pilot error stemming from spatial disorientation. This happens when pilots cannot interpret altitude, typically due to weather. This was entirely avoidable and I am still angry about it.

A trained pilot compensates for spatial uncertainty by relying on their flight instruments. The data is something you can trust when your senses are failing you.

In times of economic uncertainty you also need something to latch onto.

Short of that and you’ll likely panic, make poor decisions or stick your head in the sand to avoid pain. You’re human; it’s baked in the code.

You need help in this situation. That can be a data set, a process, a framework, an investment manager, a puppy…whatever. Anything that can help calm your nerves and ground your decision making will help.

In a bear market, basic math tends to work the best. This might be a 10 year earnings multiple or cash flow (or dividend) yield. Some objective threshold that gives you confidence when others are trampling each other to get out the door (like the market last week).

This is (partly) why high growth, yet unprofitable software companies have been taken out to the woodshed. As it turns out, a sales multiple is a flimsy vessel unsuitable for gale force winds.

For example consider a cash burning tech stock that IPO’ed at 50x sales and is now trading at 15x sales. It’s down 70%, surely it’s a good buy now. Is it??

Few actually know, because we can’t see the cash flow.

Sales multiples are sloppy short hand for valuation work. To truly assess value of a high growth company you need to back into future profitability by looking at unit economics. Do they make money? Do they have pricing power, or is it all smoke and mirrors?

Then you need to make assumptions about massive growth, operating leverage at scale, future stock based compensation (share dilution), competition and a million other variables.

SIDE NOTE: This is why I love real estate investing - if the tenants are “sticky” and the maintenance capital is light - there are FAR fewer (and easier) variables to consider.

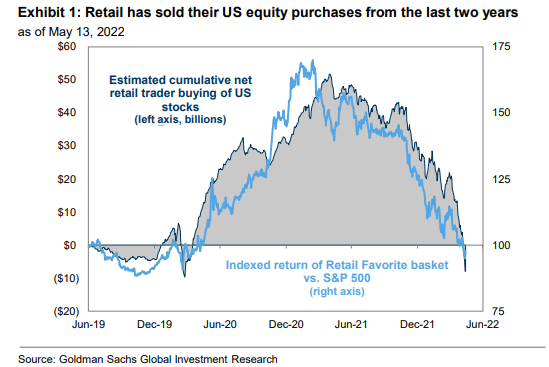

Short of that detailed analysis you’re just hoping the price will rebound. This is why retail investors are absolutely panicking / fire selling this year:

The average person does not have the time or temperament to fully understand what they own. They bought on a whim based on narrative and they’re even quicker to sell when a scarier story emerges.

For some, this was absolutely the right decision. If you a purchased a pile of garbage that’s currently on fire… by all means, dump away. But if you bought the overall market - or a great company - at peak pricing that can earn its way out of this, selling was probably a mistake.

Buying The Dip?

But how do you know to hold or - or harder still - buy more when the sky is falling? Well, at the sake of belaboring the point / metaphor, you need your own altimeter; some sort of horizon to help you orientate.

In other words, try to grasp onto an asset class you know cold or something you know to be TRUE.

For example, you don’t know if a bear market will tank an investment 20%+ from here and you don’t know what interest rates will be in a year. However, perhaps you know that paying 12 times cash flow for a growing business with a reasonable moat has almost always been a great deal. That’s something you can lean on.

Reliable Income

Or maybe your source of confidence is ACTUAL CASH you’re receiving from your investments. If your asset is doling out income but Mr. Market says its worth 20% less today than yesterday does it even matter? It’s a lot easier to tell the market to pound sand and avoid panic when you’re collecting dividend checks.

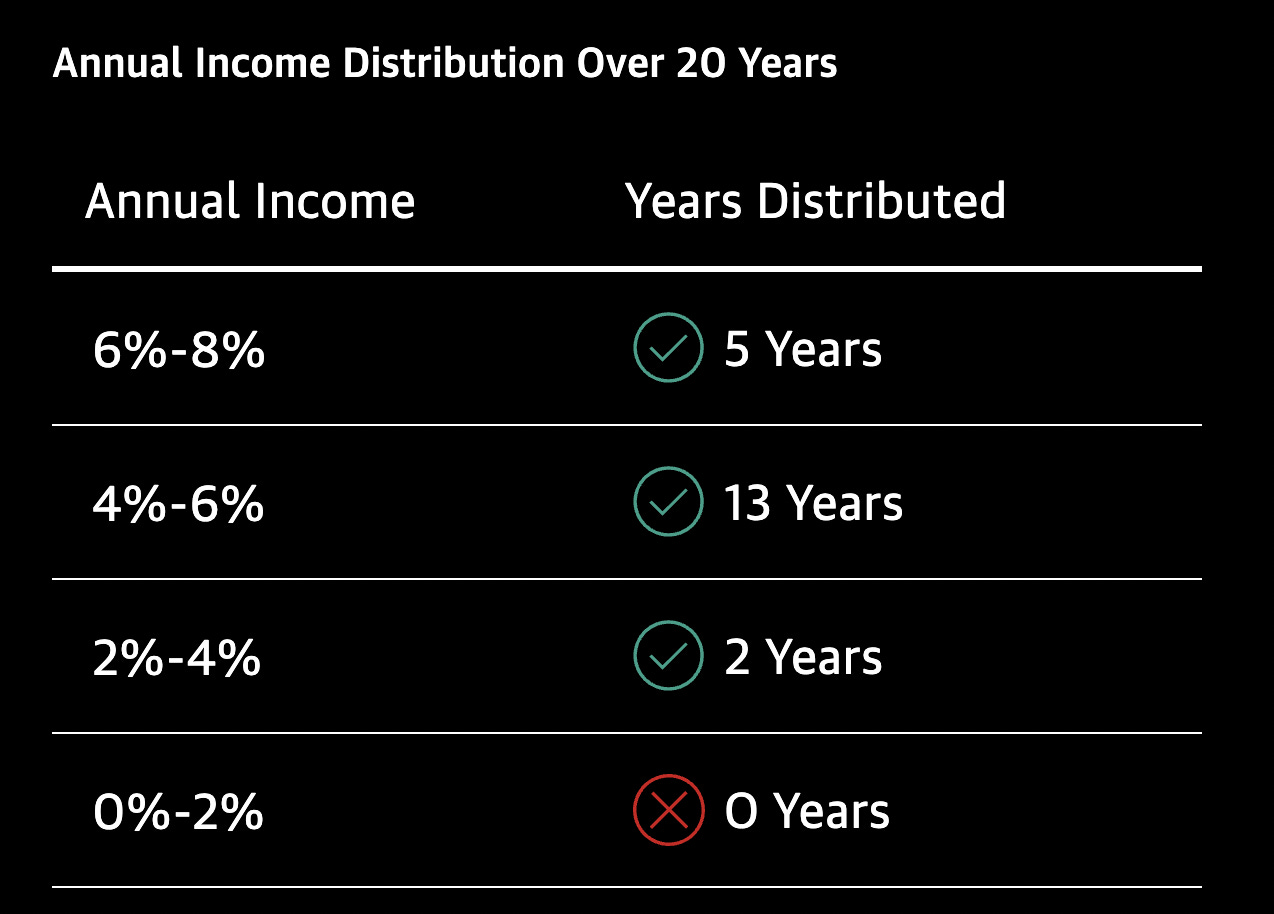

According to NFI-ODCE, over the last 20 years, institutional (high quality / lower leverage) real estate has consistently distributed compelling income - at least 4% over 18 of the past 20 years)1.

This is in spite of recessions, wars, terrorist attacks, the GFC, a global pandemic and even history’s worst real estate crash. The income kept coming and the price eventually recovered.

Price Per Pound

After the GFC, I was working on a joint venture office deal that Baupost - large Boston hedge fund - was looking to purchase in San Fransisco. I asked what cap rate they had it under contract for. The managing director told me he had no idea as the office tenants kept defaulting. He said that Seth Klarman (founder) just knew $200 per square foot for downtown SF real estate was cheap enough.

I assure you, there has never been a fogger time to invest in real estate than shortly following the great recession, yet Klarman knew the odds of things working out at that basis were extremely high. World-ending narrative be damned, they were buying solely on “price per pound”.

This works in real estate because the inherent land value and the replacement cost of the structure are “true”. We know they have value and can reasonably estimate future rent.

This is tricker with companies. Book value used to work but accounting games and intangible assets killed that value signal. However, it helps to remember that eventually every business will trade at 12x CASH FLOW. I’m not suggesting you should be dogmatic about value vs. growth. If it’s a quality business, you see a clear path to high cash flow and are being rewarded for the duration risk, that sounds like a horizon you can focus on.

Are any of these suggested metrics laws of nature? No! The game can change and - however improbable - the altimeter could be broken. But in the haze, it’s the best shot we’ve got.

Brad Johnson

NCREIF, 20-year period ending December 31, 2021.